On Wildfires

Can we still hope for the garden?

This month, Qabb Elias educational garden caught fire. Thanks to our preventive action and the intervention of a local hero, it could be contained. However, wildfires address the question of the possibility of the garden: up a certain temperature, wood becomes a fuel. Hence, can we still plant gardens while climate is warming up? A meditation based on the reading of the historian of environment Stephen Pyne and the Evangelical theologian Jacques Ellul.

A happy ending narrative

Let’s begin with a story.

Qabb Elias Educational Garden was an A Rocha project led by Martin BERNHARD between 2015 and 2018. However, after it was handed over to the municipality, the garden remained closed, and its beauty began to fade.

A very local solution had to be found. In July, Guillaume DE VAULX conducted an inquiry in the surroundings of the garden to involve the neighbors in its management. As a result, it was decided to propose to the municipality the appointment of Abd al-Nasser KHUTAYBI, a local hair-cutter living in front of the garden and having his shop in the same street, as the manager of the garden and representative of the neighbors. As a hair-cutter, he knows all the neighbors and talk with each of them monthly. Used to take care of the hair, he would also take care of the grass. A perfect candidate.

After a few rounds of negotiation with Jihad AL-MUALLIM, the president of the municipality, the appointment of Abd al-Nasser was accepted. We brought and set up hoses, filled up water tanks, and gathered the children of the area in order to take care of this garden that would be theirs.

It was Thursday, the 3rd of August, and we scheduled an appointment for Sunday to officially hand over the keys of the garden to the neighborhood representative. Finally, after being closed for 5 years, the garden would open its gates to the public.

However, on Friday night at 1am, we received a call from Abd al-Nassir: the dry grass in the lower part of the garden had caught fire, and the garden was burning!

Qabb Elias educational garden on fire – © ‘bd-Nsr

Don’t worry, the water system is fixed, and the tanks are full. Please, act quickly.

Abd el-Nasser fighting fire – © ‘bd-Nsr

Abd al-Nassir and his friends trespassed the fence, opened the taps, and fought the fire, which remained contained to the lower part of the hill.

Traces of the night of fire in Qabb Elias educational garden – © GdV

Abd al-Nassir had passed the trial by fire; he deserved his position. The garden was in good hands.

The next morning, he held the keys, and children came to clean the ground and water the trees of this miraculous garden, a survivor of a “night of fire.”

The more tragic global story

All the forests of the world are currently experiencing prolonged nights of fire that no army of firefighters can halt: Mediterranean forests, of course, as seen in California, Spain, or Greece, are burning, but so are boreal forests in Siberia and Canada, as well as tropical habitats like in Maui (Hawaii). Due to global warming, no woodland or meadow remains shielded from the risk of fire. As its green cover no longer aligns with the new climatic order, all of nature is ablaze. With fire, we recognize that no living being is any longer safeguarded from destruction. A survey published in this month’s issue of Science describes how large mammals from the late Pleistocene became extinct due to wildfires linked with the correlation between global warming and human activities.[1] And nowadays, megafires are obliterating vast habitats, along with their inhabitants.

Yet, hope persists for the garden, with the garden seen as an ideal place to inhabit. Consequently, we are restoring natural sites to establish gardens and nature parks. However, from a fire perspective, does this imply the potential for more fires? After all, since fire thrives on carbon, is cultivating a garden more than accumulating fuel for future fires?

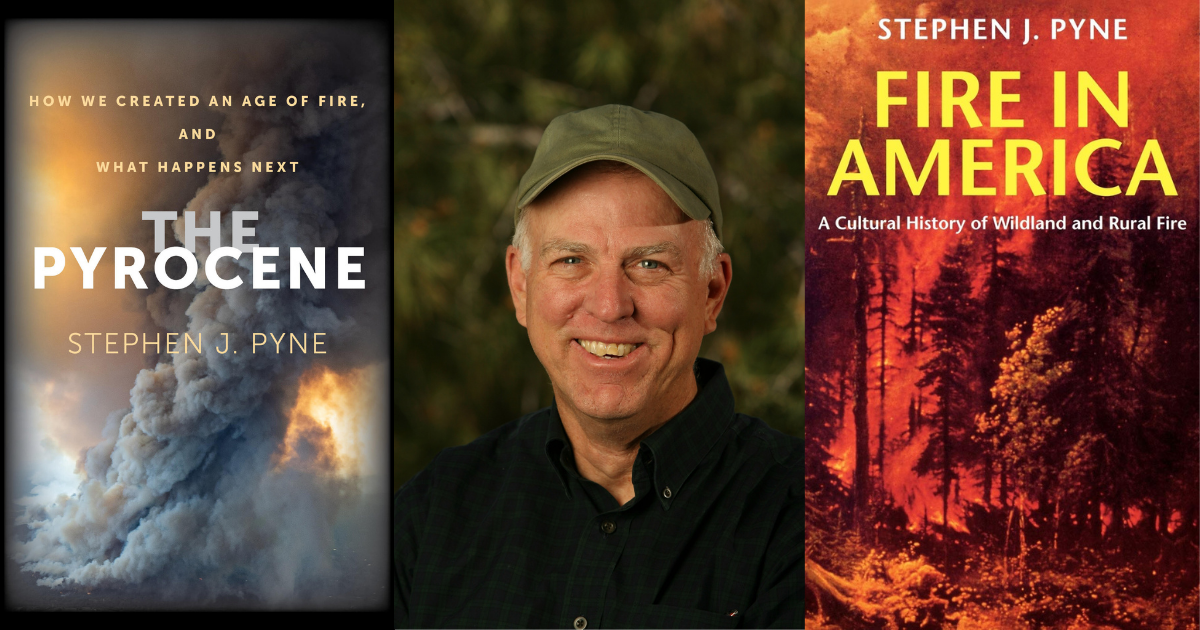

Stephen Pyne and the equation biomass=fuel

There exists a chemical duality to carbon: it serves as the central element in the metabolism of living beings, and at the same time, it plays a crucial role in combustion, as highlighted by Stephen Pyne:

“Combustion, a reaction which, simply put, takes apart what photosynthesis brings together.” (Fire, p. xvi)

Here is the reduced formula:

C6H12O6 +6O2 + 6H2O >> 6CO2 + 12H2O

glucose + oxygen + water >> carbon dioxide + water

This environmental historian dedicated his research to the study of fire. In the initial volume of his work on fire, titled Fire: A Brief History, he underscores the intrinsic connection between life and fire:

“The biomass can exist as either fuel or forage” (p. 78).

Plants can either burn in flames or nourish animals and engage in their metabolic processes.

“In the paddock as in the wild, [animals] compete with fire for the available biomass.” (p. 77).

Hence, one should avoid romanticizing nature: it contains fire, wildfires emerge as a direct consequence of forest growth. Despite perceiving fire as a mean of destruction for habitats and living beings, it is essential to realize that fire is an outcome of life itself:

“Life can exist without fire. The oceans prove that. But fire cannot exist without the living world. The chemistry of combustion has progressively embedded itself within a biology of burning.” (p. 14)

Fire is a phenomenon unique to Earth, a living planet distinguished by its carbon chemistry and its oxygen-rich atmosphere, which was brought into being through bacterial and plant photosynthesis. Flames flourish where living beings exist.

Furthermore, it’s imperative to acknowledge that fires are infrequent without human involvement. In fact, whereas the chemistry of fire necessitates a living planet, its frequency is heavily influenced by human control of the spark; hence, fire is primarily an anthropogenic occurrence.

“Fire and humanity pushed and pulled each other around the globe” (p. 25).

Hominids indeed populated the Earth, harnessing fire to clear land.

Prometheus unleashed, and fire bound

If our history as living beings and hominids is so intertwined with fire, why do we harbor such a negative sentiment when confronted with natural fires?

Stephen Pyne distinguishes three moments in his history of fire: 1° the natural fire, primarily ignited by lightning, 2° the aboriginal fire: fire is harnessed by humans through control of sparks, 3° Industrial fire: fire is confined within chambers, and combustion becomes the driving force behind all movement and production.

The contemporary viewpoint on fire stems from the perspective of an industrialized and urbanized civilization, both towards the natural phenomenon and traditional practices. First, the combustion in the industrialized world no longer revolves around wood, but instead coal and oil:

“’Industrialization’ signifies… the combustion of fossil biomass.” (p. 155)

While aboriginal fires are fueled by biofuels, industrial fires consume fossil fuels. This implies that burning plants is no longer considered productive. Pyne cites Pliny the Elder who stated:

“Fire is an immeasurable, uncontrollable element, and it is difficult to say whether it consumes more or produces more.” (p. 121)

With industrialization, it was believed that the ambiguity of fire’s power was resolved: while burning wood is purely destructive, creative power only arises from the combustion of fossil fuels. This assumption was flawed: global warming now makes it evident that industrial combustion of fossil fuels wields globally destructive power.

Subsequently, in our efforts to curb global CO2 emissions, we fear the substantial emissions generated by wildfires. We put natural fires in competition with industrial fires, and our productivity-oriented mindset laments the unproductivity of such emissions; they burn and release carbon into the atmosphere to no avail. It’s pure destruction. However, can economic growth justify climate deregulation more effectively than a natural fire?

Secondly, fire has become less of a phenomenon, as it now burns within enclosed combustion chambers (p. 117). Consequently, few still gaze upon flames in hearths, given that half the world’s population resides in urban areas, where fires are prohibited. Pyne highlights the paradox in the relationship between urbanization and fire:

“Modern cities remain ecosystems driven by fire. Fire’s influence is pervasive, yet fire is almost entirely invisible. Its fuels exist as liquids and gases; its combustion occurs within specialized chambers and machines.” (p. 115-6)

Although everything in the city originates from fire, fire remains unseen. In a civilization where fire has receded, open flames evoke terror. And this terror is that of truth. While we are captivated by forests and their slowly maturing trees that embody centuries of stability, our civilization is constructed on immediacy, founded on fire and the present-day destruction of millions of years of biomass accumulation (coal and oil burned in engines and factories).

Intellectually, wildfires are excluded from our value system, but climatically, they have become the norm. A civilization that consumes biomass accrued over millions of years has forged the climatic conditions that foster wildfires. How can forests and gardens thrive in a civilization built upon fire?

Jacques Ellul. The Garden of Eden or the New Jerusalem?

Given that we cannot evade the dual nature of biomass – serving as both sustenance (and habitat) for animals and fuel for fire – should we forsake living habitats to seek refuge in the mineral realm of cities where fire is absent? This question has historical roots, a similar one having been raised by the Jewish people in the Bible. Indeed, reflections on the hereafter revolve around the dichotomy of the garden and the city: Eden or the New Jerusalem? The inquiry then becomes:

Should we also relinquish the ideal of the garden and replace the living Garden of Eden with the mineral New Jerusalem, as the book of Ezekiel suggests? In the New Jerusalem, there is no fire, but there is also no garden.

The environmental thoughts of the Evangelical theologian Jacques Ellul are grounded in this theological duality, as presented in his book, The Meaning of the City (in French, Sans feu ni lieu, no fire no place). The garden is a gift from God, while cities are human constructions. In contrast to Greek philosophy, the Bible portrays God creating Adam and Eve in a garden, while cities symbolize humanity’s defiance against God, exemplified by Nineveh. In Ellul’s view, cities transform from places where technologies serve as tools to technological systems that leave no room for human freedom. Metropolises, especially the banlieue – mundane and uniform spaces – embody inhumanity, the antithesis of the countryside. Cities are domains of artifice, where nature is vanquished. Yet, God spared the people of Nineveh. So, should we also forsake the garden and place our hope of salvation as city dwellers?

It’s crucial not to overlook that God spared Nineveh for its “hundred and twenty thousand people who cannot tell their right hand from their left – and also many animals.” (Jonah 4:11). God’s rescue of Nineveh was not for the sake of its wise men, but for its (ignorant) living creatures.

To retain hope for the garden – a living habitat for living creatures – within an industrialized and urbanized civilization, we must embrace the equation: biomass = fuel, and the associated risk of fire. Only a living habitat is suitable for living beings and can cater to them. However, it is important to acknowledge that the biomass of the garden can potentially become fuel for wildfires. Thus, aspiring to the garden requires us to embrace the risk of fire…

[1] O’Keefe and al., “Pre–Younger Dryas megafaunal extirpation at Rancho La Brea linked to fire-driven state shift”, Science, Volume 381 | Issue 6659, 18 August 2023.